The Latinx Roots of Public Art

Hispanic Heritage Month takes place from September 15–October 15 and is celebrated in many countries around the world, including the U.S. and the U.K. According to the 2021 Census, over a quarter of a million Latinos live in the UK, comprising the eighth biggest ethnic group born outside of the UK in London. Despite this, there is not even a box to describe Latinidad on its demographic forms. As an international Latina student, I have scrolled and scrolled through the available options to find something that describes me, only to resign myself to selecting the anonymity of “other ethnic group.”

This fall, I am excited to be working with Paint the Change. A London-based organization working through public art to advance social justice, I see firsthand how this NGO uses street art as a tool for the global empowerment of marginalized groups. We are committed to uplifting the lives, work, and legacies of Latinx artists. In the context of cultural looting, Latinx street artists play an especially critical role in reclaiming and disseminating the unique histories and artistic traditions of their cultures to their communities. With Hispanic Heritage Month coming to a close, we’d like to examine how these legacies can be felt in cultural self-identifications, memory, and artists’ reimaginings of a more radical future today.

The Birth of Street Art for Social Justice: A Tribute to Diego Rivera

In order to fully appreciate how monumental the use of public art is for change, one must go back to credit Diego Rivera, one of “Los Tres Grandes,” or The Three Great Ones, that founded Mexican Muralism. His street murals to communicate cultural pride and political alternatives spread throughout the world, with his influence seen today in all public spaces with accessible, thought-provoking art.

Diego Rivera was born in Guanajuato, Mexico, in 1886. A giant of Mexican culture, his legacy is felt in art, activism, and cultural imagination as a political revolutionary and genre-bender who challenged public consciousness and established a global movement towards murals as a form of artistic political communication.

Rivera’s “The Marriage of the Artistic Expression of the North and of the South on This Continent,” also known as “Pan American Unity,” advocates greater understanding and cultural solidarity between American countries. (Photo credit)

Rivera came of age in the shadow of the Mexican Revolution and WWI. With this came a devout political consciousness which called him to challenge the status quo through incorporating protests against social stratification, capitalism, and the totalitarian nature of the church into his work. Having been formally trained in art in Mexico and Europe, his work combines traditional Mexican cultural heritage and social struggles with European techniques (i.e. Italian frescos of the 14th and 15th centuries). After the Mexican Revolution, the new government was eager to support public art for education. With civilians who couldn’t read or write, large-scale murals were seen as an effective medium for transmitting messages strengthening cultural identifiers towards a greater sense of national unity, aligning with Rivera’s firm belief in making art accessible.

Upon Rivera’s return to Mexico in 1921, he was commissioned for several murals which he used to demonstrate the beauty of Mexican culture and a hopeful, post-Revolution future. Like many artists focused on social justice, Rivera’s work was both celebrated and opposed. One major example of this can be seen in his Rockefeller-commissioned mural, “Man at the Crossroads.” Commenting on technological advancements and social division, Rivera placed an image of Lenin at its center, forcing the viewer to confront the juxtaposition between how rich elites and the lower classes do or do not experience war. Lenin was portrayed as holding hands with a diverse group of workers, making room for a new, utopic vision of a socialist world. Proving too provocative for the Rockefeller Center, Rivera was fired and the project destroyed before it could be completed. Despite this pushback, he went on to make a recreated version of this project in Mexico City, calling it “Man, Controller of the Universe.”

“Man, Controller of the Universe” as seen on display in Mexico City’s Palacio de Bellas Artes. (Photo credit)

Throughout his life, Rivera challenged convention by democratizing art, its themes, and spreading pride in Mexican peoples and culture. He proved the subversive act of expressing yourself in public spaces to be an effective medium to empower and engage communities. Rivera’s legacy can be seen across the globe in the very existence of public murals today. His influence is especially felt in Latinx street artists who carry on his tradition by using their talents to advance social justice with distinct pride in their rich heritage.

A Latino Living Legacy - Today’s Changemakers

Rivera’s work provided a foundation. Now, Latinx street artists are building upon his tradition by creating their own. With vastly different creative methods and messages, the following artists reflect the diverse manifestations of Rivera’s legacy and represent a new wave of modern public art to know, follow, and support.

Paola Delfin

Paola is a Mexican artist who paints in black and white. Highly influenced by illustrations, she aims to make her work universally appealing while communicating charged messages of the strengths behind Latina femininity. Resiliency is a common theme throughout her pieces, which frequently depict the female form.

“Mis Raices/My Roots” by Paola Delfin. (Photo credit)

Johanna Toruño

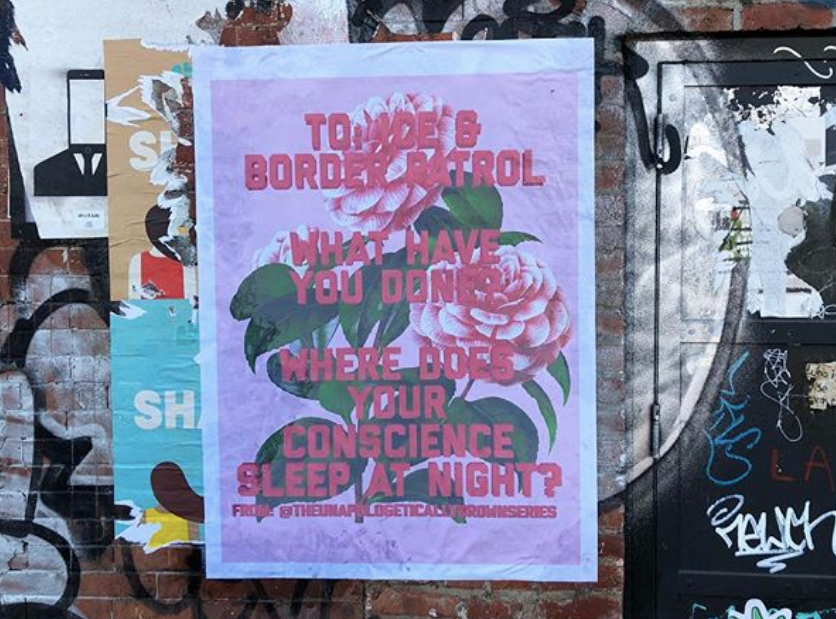

Originally from El Salvador, Johanna migrated to the United States at a young age. She works under “The Unapologetic Street Series,” with her art using politically-charged language and florals referencing the environmental diversity of El Salvador to encourage public engagement with uncomfortable topics. She has become a public figure advancing queer Latinx visibility and accessible art, using her platform to question inaction on climate change, advocate for Palestinian solidarity, uplift Latinos in U.S. society, and advance these diverse issues’ solidarity.

One of Johanna’s posters as seen on the street. (Photo credit)

Bastardilla

This anonymous artist grew up on the streets of Colombia. Having first entered the world of public art through graffiti, she has chosen to preserve her anonymity despite international acclaim to maintain the sanctity of the messages in her work. She frequently depicts feminist messages condemning gender-based violence in her art, focusing especially on the struggles and victories of South American women in their local contexts.

“Minga!” by Bastardilla. In Quechua, the term ‘minga’ references cooperative work. (Photo credit)

Puriskiri

This Bolivian artist advocates for global gender equality and environmental justice while linking these movements to the importance of local action through references to regional folklore and Bolivian culture in his work. He firmly believes in empowering his community, conducting workshops with children to facilitate the rediscovery of traditional techniques and themes. Puriskiri understands public art as an act of political responsibility and emphasizes the beauty of the everyday in his work. His pseudonym is Quechua for ‘walker.’

One of Puriskiri’s many murals depicting Indigenous Bolivians. (Photo credit)

Honoring the Past Through the Present

In a world with vastly different education levels across gender, class, and region, making art accessible is critical to building an inclusive society. Diego Rivera’s pioneering work brought the techniques of ‘high art’ to everyday spaces, questioning the status quo and depicting Mexicans in their full cultural complexities. The influence of Rivera’s Mexican Muralism can be seen through Latinx street artists' present-day commitment to continue the democratization of political thought through public art. By taking over the streets, these artists engage communities around the world in new conversations and establish the roots of social change. As allies in creating a better world, our job is to appreciate, question, and bring these conversations forward, this Hispanic Heritage Month and beyond.