Frogs, Transformation, and Social Justice: Apolo Torres’ Art for Change

By Daniella Angulo

Apolo Torres (@apolotorres) is a Brazilian street artist who worked with Paint the Change in 2016, on the #EducationIsNotACrime project, which raised awareness of the denial of education to the Baha’i religious minority in Iran. His mural depicting a young girl reaching for knowledge still stands in São Paolo. Since then, his career has reached new heights, with his work bringing attention to social justice issues in Brazil and around the world. We caught up with him to chat about his current projects, areas of interest, and experiences as someone working in public art.

This interview was edited for clarity

(‘Nina.’ Credit: notacrime.me)

You’ve just come back from the Museum Murals festival, where you were inspired by the artist Anya Jassen to create a mural commenting on coming of age. Can you speak a bit about your experience with this project?

This festival is very different from others. It bridges the museums and the city’s murals, which are two worlds that don’t often mix. We looked at museum collections and picked one work to reinterpret through a mural. It was an interesting way of working, and it was nice to build connections with the museum and community. Community connections often happen, but not with the institution.

This goes back to “Co-Existence,” my first series. It was about the relationship of my city with its waters. São Paolo used to be a tropical forest. It’s home to many rivers, which the city has been built over. Building roads was easiest on the valleys, but this is where the water goes through.

So they put the rivers underground and built roads over them. Sometimes, when you’re walking on the street, you can hear the water underneath. When it rains heavily, these channels and pipes can’t hold all the water, so they flood.

“Co-Existence” depicts the human impacts of floods. It was initially about my city’s relationship with water in a very literal sense. We tried to build the city over it, but nature prevails and the rivers say no, I’m still here. You can’t hide me forever.

Then I heard this song talking about how cities grow. He sings, “I'm gonna build my castle on that hill over there, where 100 years from now it’s gonna be a shoreline.” I realized this work wasn’t just about the present or past, but also looking forward.

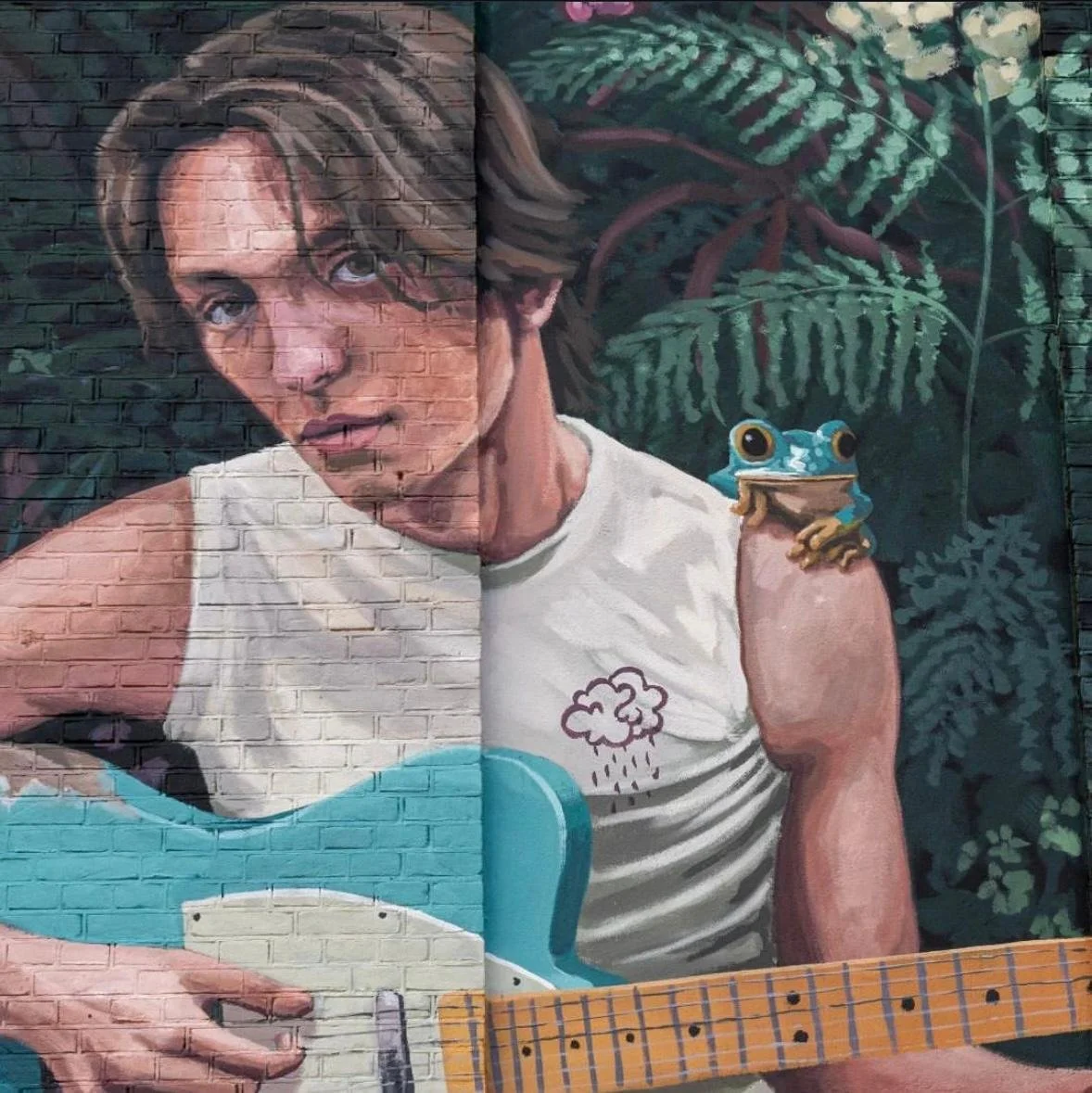

When I’d extracted all I could from these visuals, I came up with the frog. Frogs begin as aquatic beings who then grow out [of the water]. It became this landmark of shifts into new directions. My daughter was born that year, so it also represents a landmark of abrupt change in my life. The museum had art from Anya Janssen, who portrays subjects with their pets. I brought back the frog because it made sense in this context—it became his pet.

(‘Coexistência II.’ Credit: apolotorres.com)

So even though the environment may not be your main focus at the moment, there’s still references to it if you know how to look.

Lately, my work is about the city, but it’s shifted from water and environment to labor and housing problems. These issues spark my attention a bit more. The homeless population has grown really fast—there are 40,000 homeless people in the city, and 600,000 empty apartments—so my latest works are about that. The environmental issues are always in the back of my mind. I’m working on a series about gold mining and deforestation, but they’re works in progress.

These are huge issues to tackle through art! How do you interact with and get inspired by these different subjects?

“The themes are usually from the news. That’s what got my attention with the first series. Last year, my studio was in downtown São Paolo, where most of the homeless population is. It became part of my daily life. Being confronted with that reality, you can’t ignore it—hence my work now on homelessness. I think that’s how it goes.

Mining and deforestation are further from my daily life. It’s mostly in the Amazon, but the effects have become really apparent. We’ve started seeing rivers completely transformed and how that’s shaped the landscape. I had to paint something about it.”

How has your perspective on the impact of street art changed over time?

When I started, I was less aware of the power street art has to affect others. I thought it was background noise for most people, but that’s not the case. I’ve had all sorts of reactions to my work—including backlash—by the public. All these years have made me aware of the power it has to affect and communicate with people.

Ultimately, I think my ability is for making people think about subjects they weren’t before. Real change cannot be achieved by someone doing something alone. It doesn’t matter if it's a mural, song, any art form. Artists create a spark. To grow, it needs collective action. I realize it only goes so far.

(‘Imersidão.’ Credit: apolotorres.com)

That’s a very nuanced perspective, thank you for that! Can you talk a bit further on the backlash you’ve received as a result of your work? How do you deal with that, as an artist and human?

Some people don’t seem to be able to look past their perspectives, but I can‘t control how people interpret.

I realized this because of a piece on freedom of expression. My project had nudity and the neighborhood wanted it erased. I painted a man who has a hidden bird cage on his back. I received emails from ornithologists (bird experts) who were angry that I painted a caged bird. It’s a metaphor, it’s not literal!

Everyone will always look from their lens. Because ornithologists care about birds, that piece for them is about trapping birds, not expression. If I try to make something 100% good for everybody, it’ll be good for nobody.

I’ve got to keep doing my thing, and at least these conversations arise. We can talk about how capturing birds isn’t okay, as long as you understand that murals are an opportunity for us to discuss this. I’m not trying to make a point or solve problems with one image. It’s an opportunity for us to come together and discuss. If we achieve that, my work did what it was supposed to.

(‘Livre Como Um Pássaro.’ Credit: apolotorres.com)

Thank you to Apolo for taking the time to reconnect! Hearing Apolo speak so passionately about the environmental and economic injustices he focuses on in his work was an enlightening experience. Even though the subject matter of his pieces are rooted in the Brazilian context, they address globally connected issues. Eight years after #EducationIsNotACrime, we’re excited to continue touching base with our selected artists to share the diversity of their experiences in public art through a series of interviews.